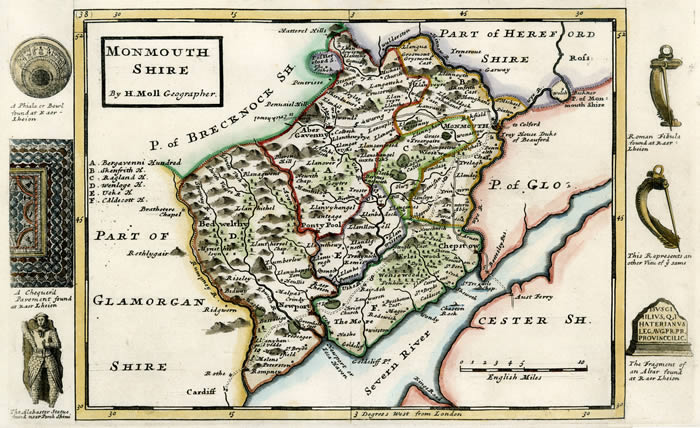

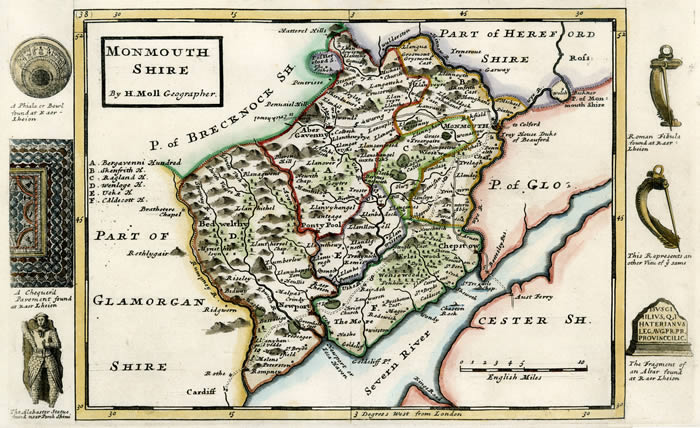

Watercolour drawing by N Young

Watercolour drawing by N Young

the charge made by the museum for photography

and displaying the photo is beyond our budget.Found 350 years ago

This alabaster statue was discovered around 350 years ago in a quarry between Caerleon and Christchurch. It was found near a large stone coffin containing a skeleton inside an iron frame wrapped in a lead sheet.

Mentioned in Camden's Britannia 1695

We first became aware of it when we transcribed the text relating to Caerleon from Camden's Britannia for this website (see below). The passage referred to an illustration of the statue elsewhere in the document, but we did not have the relevant pages and all our efforts to track down the pages were fruitless.

However the description was intriguing:

a gilded Alabaster statue of a person in a coat of mail; holding in the right-hand a short sword, and in the left a pair of scales. In the right scale appeared a young maiden's head and breasts; and in the left (which was out-weighed by the former) a globe.

Given to the Ashmolean Repository in 1693

By the time Camden's Britannia was compiled, the feet, right arm and scales had broken off, but the writer described it as tolerably well preserved with some of the gilding remaining. The writer added that the statue was given by Captain Matthias Bird to the Ashmolean Repository at Oxford.

Out of the Blue

A few weeks ago we received an email from local historian Richard Frame with the subject heading: "Have you seen this?" When we opened it - wow! - there was a picture of the statue. Richard had come across it while on a visit to the Ashmolean Museum. It has heen sitting (or standing) there for over 350 years! Why hadn't we thought of looking there? Item AN1685 A(2).28, described as "Figure in a coat of mail, Caerleon, Wales, alabaster (originally gilded). An account of this figure was included in the 1695 edition of Camden's Britannia. The figure itself was presented to the Ashmolean in 1693."

Illustration from the 1805 edition of Camden's Britannia.

Illustration from the 1805 edition of Camden's Britannia.

Who does it depict and why was it buried there?

It is probable that the scales represented the weighing up of justice and the sword power and protection. Maybe it was buried near the coffin as a sign to say the deceased would get what he/she deserved in the next world - good or bad. Maybe the deceased had been a figure of some authority administering justice.

Greek Goddess?

In 1695 the writer suggested maybe it depicted the Greek Goddess Astræe, daughter of Zeus and Themis, personification of justice, innocence and purity. The figure would certainly seem to display some female characteristics.

Angel?

We think it could possibly be St Michael, and that what at first appears to be a shield behind the figure could have been wings. There are many statues showing him holding a sword in the right hand and scales in the left with a woman in the one side outweighing a man in the other.

What do you think?

Just over 300 years ago the writer said, "I must leave the explication to some more experienced and judicious Antiquary." Maybe you have some ideas. If so please contact us via the form below.

Update

Rodney Hudson, an expert in this field, has examined our pictures and has sent us a detailed report on the figure. Here is a brief summary... "The armour and hat suggest a date in the range 1480 to 1530. It is likely that this is a depiction of St Michael and there may have originally been a dragon at his feet. It was probably a monument for someone who had died and it's original siting could have been at Christchurch. It seems likely that it was deliberately broken during the Reformation (around 1535) when religious effigees were destroyed. It would then seem to have been dumped where it was found. The coffin found nearby may have had no connection with the statue.

"If it was a monument to someone who died, who might that have been? It must have been a member of a wealthy family. The first that comes to mind is the Herbert family from St Julians, but probably we will never know... "

Update 2

The Ashmolean Museum still has the Book of Benefactors in which donations to the museum were recorded. The entries were written in Latin, here is a translation of the relevant 1693 item:

"Matthew Bird, a ship's master from Caerleon in Monmouthshire, gave the Museum a figure in a coat of mail, sculpted from alabaster, which was once covered in gold leaf, holding a sword, still fully preserved, in its right hand and, in its left, a pair of scales. The right pan of the scales, which is the heavier, shows a girl's face, the left one shows the globe of the Earth. It was dug up in about 1660 near the town of Caerleon or, in Latin, Isca Legionum (where the Second Augustan legion used to be stationed) near the spot known as Porth Siny Kran."

Curious that there is no mention of the "large coffin of free-stone; which being open'd they found therein a leaden sheet, wrap'd about an iron frame, curiously wrought; and in that frame a skeleton". (See the original text from Camden's Britannia low down this page.)

Update 3

Dr. Maddy Gray, Reader in History, University of Wales, Newport, has sent us the following detailed thoughts about the figure:

"Looking again at your Mystery Picture of the Month 325, I’m convinced that it is St Michael weighing the souls of the dead. The clincher is the description in Camden’s Britannia of the figure in the right-hand pan of the scales - it’s a pity that the carving has since been broken and that detail is lost.

"It looks like a late medieval carving from a tomb chest - the same overall design as the ones in Abergavenny. These carvings were produced in huge quantities in workshops near the alabaster quarries in Derbyshire and Nottingham. You ordered them more or less in kit form - you asked for an effigy of yourself in your best clothes, your dearly beloved late spouse in his armour, plus an assortment of carvings on the side panels - say 4 weepers, 4 angels with shields (to be painted in your family heraldry plus the heraldry of distinguished relatives), saints Catherine, Margaret, Christopher, Michael ... and it probably arrived in a flatpack with the wrong size allen key and instructions in a foreign language!

"So while I agree with Rodney Hudson about the identity of the figure, I do think that the carving is likely to be connected with the coffin. It’s certainly an appropriate carving for a tomb. The idea of St Michael weighing the souls of the dead comes originally from Egyptian iconography but it was quite common in late medieval Christendom. There are wall paintings at South Leigh (Oxon) and Slapton (Northants) - see http://www.paintedchurch.org/doomcon.htm for links to these and others. On the painted panels from the rood screen at Llanelian-yn-Rhos, near Colwyn Bay (a church well worth a visit when you are tired of the beach!) Michael is accompanied by the Virgin Mary who is putting her rosary on the scales to weigh them down on the side of salvation. On the other side of the painting the Devil is dragging down the scales. The figure in the pan on the side of the Virgin Mary is clutching her skirts and pop-eyed with terror. On the Devil’s side the figure in the pan is already turning into a demon.

Detail from the rood screen at Llanelian-yn-Rhos, near Colwyn Bay

Detail from the rood screen at Llanelian-yn-Rhos, near Colwyn BayThere is a very faded wall painting of the same scene just up the Usk valley in Llangybi, but the figure of the Devil is obscured by a later painting. At Tremeirchion in Denbighshire there are some fragments of stained glass - a naked figure sitting in what looks like a shallow pan and a little demon who seems to be sitting in a swing. These are probably part of St Michael’s scales. On the other side of the Vale of Clwyd, at Derwen, St Michael and his scales are on the churchyard cross.

Churchyard cross at Derwen

Churchyard cross at Derwen "The thought of being weighed in the balance and found wanting is certainly a scary one. The fifteenth-century poet Llywelyn ap Hywel ab Ieuan ap Gronwy of Llantrisant (Glam) had this to say about his worst fears:

Llun Mihangel a welwn

A baiys a bwys hwnn

Y gwr du yn hagr a dynn

A llaw winau yn llinyn …

(I saw the image of Michael and the sinner he weighs:

and the ugly Black One, tugging at the thread with his swarthy hand:

and the gripping on the other side, loaded down with Mary’s rosary;

and the soul there, dying, teaching a sharp lesson about good works.

May Mary the meek and fair receive him; in the fire she knows him.

When I go to Michael, I shall tug Satan’s fork,

and by my soul I shall wish him ill luck in the scales!

May Michael and Mary, for fear of the icy cauldron, be successful against him!)

"But he clearly expected to be saved at the end. St Michael represented the church militant, the conqueror of Satan. His place was where the danger was greatest – so he is here not to terrify but to defend. And the Virgin Mary would be on your side as well - as Eamon Duffy says, she had a soft spot for the worst scoundrels. We are apt to view these pictures of judgement through the distorting lens of chapel hellfire-and-damnation preaching. If you look carefully at the picture of the Last Judgement at Llanelian you will see what the angels are carrying like banners: the cross, the spear and all the other artefacts from the Crucifixion story. They are there not to terrify but to reassure: because of them, even sinners can get to Heaven.

The painted panels from the rood screen at Llanelian-yn-Rhos

The painted panels from the rood screen at Llanelian-yn-Rhos "St Michael was actually expected to look after you after death. The special Mass of St Michael was the Mass said for the souls of all the dead. In early sixteenth-century Brecon a stipendiary priest was paid 26s 8d a year (roughly equivalent to about £2,500 in modern money) to celebrate the Mass of St Michael every week in the town charnel house. This was where the bones were kept after they had been dug out of the churchyard to make room for new graves. Not the most pleasant of jobs - but it shows that even the anonymous dead were still thought to be important.

"If the carving and the coffin and skeleton are connected, how could they have ended up in such a strange location, outside consecrated ground? The most likely explanation is some sort of iconoclastic purge in the sixteenth century or possibly during the Civil War and Commonwealth in the mid-seventeenth century. Not all tombs with carvings of saints on them were damaged or destroyed but a lot were. But why move the body as well? Chest tombs were designed to look as though they contained the actual bodies, but in fact the bodies were usually buried beneath the chest or in a vault. However, if the body was embalmed (and most élite burials involved embalming because of the long time it took to arrange an upmarket funeral with heralds in attendance) and wrapped in lead, the coffin could conceivably have formed part of the tomb chest. One possibility is that it was the tomb of one of the Herberts of St Julians. The earliest of that family, Sir George Herbert, died in about 1500. He had a family tradition of elaborate tombs: his grandfather and his uncle Richard were buried under magnificent alabaster chests in Abergavenny Priory and his father at Tintern. But is it likely that the family would have acquiesced in the destruction of the ancestral tomb - and still less in the desecration of the ancestral bones? The same is true of the only other possible local candidate, the family of Penrhos-ffwrdios in Caerleon.

"One other possibility - and it’s a very wild guess - is that this is the tomb of an important ancestor who had been buried in a monastic church. Tombs in monastic churches were of course very vulnerable after the Dissolution of the Monasteries and some were actually moved - for example, the tomb (and presumably the body) of Henry VIII’s grandfather Edmund Tudor was moved from the Greyfriars in Carmarthen to St David’s. Was our skeleton and carving part of an exhumation that somehow went wrong?

"And does anyone have any ideas where Porth Sini Kran and the quarry actually were?"

Update 4

Regarding the coffin, Julian Litten explained: "What they are describing, of course, is an anthropoid lead shell (see: Litten, English Way of Death, London 1991) with internal iron bands. The bands were used to assist the plumber in fixing and soldering the lead, as these anthropoid shells were made in two sections: a lower lead 'tray', with shallow sides, on which to place the corpse (usually wound in a cere-cloth shroud) and an upper 'lid', fashioned to show facial features. The lead was usually quite thin and, therefore, somewhat floppy, thus the iron bands assisted in providing a measure of rigidity when handling the item and, of course, to assist the plumber to position the lid and to solder it to the sides of the lower tray.

"I'd guess that it's either a very late medieval burial or an early 17th-century one, though probably no later than the 1640s. It was not unusual - though rare - to find stone coffins being used after, say, 1500."

Original Text from Camden's Britannia

About forty years since, some Labourers digging in a Quarry betwixt Kaer Leion Bridge and Christchurch (near a place call'd Porth Sini Krân) discover'd a large coffin of free-stone; which being open'd they found therein a leaden sheet, wrap'd about an iron frame, curiously wrought; and in that frame a skeleton. Near the coffin they found also a gilded Alabaster statue of a person in a coat of mail; holding in the right-hand a short sword, and in the left a pair of scales. In the right scale appear'd a young maiden's head and breasts; and in the left (which was out-weigh'd by the former) a globe. This account of the coffin and statue I receiv'd from the worshipful Captain Matthias Bird who saw both himself; and for the farther satisfaction of the curious, was pleas'd lately to present the statue to the Ashmolean Repository at Oxford. The feet and right-arm have been broken some years since, as also the scales; but in all other respects, it's tolerably well preserv'd; and some of the gilding still remains in the interstices of the armour. We have given figure of it, amongst some other curiosities relating to Antiquity, at the end of these Counties of Wales: but must leave the explication to some more experienc'd and judicious Antiquary; for though at first view it might seem to be the Goddess Astræe, yet I cannot satisfie my self as to the device of the Globe and Woman in the scales; and am unwilling to trouble the Reader with too many conjectures. |